ILOC Compiler

Problem Statement

ILOC code is a simple assembly language that can perform simple arithmetic, load or store memory, and output from memory. During the compilation process for traditional code languages, source code is translated into assembly code which is finally translated again into machine code that the computer can follow. Typically during this translation process some optimizations are made to speed up computations or allow the code to function on your operating system. To understand what ILOC and other assembly languages look like, the following shows ILOC instructions used to add three constant numbers together:

loadI 1 => r0

loadI 2 => r1

loadI 3 => r2

add r0, r1 => r3

add r3, r2 => r4The code above first loads constant numbers 1,2, and 3 into the registers r0, r1, and r2 respectively. Then, it adds the values in the registers together and stores them in registers r3 and r4. These registers are part of the CPU, or central processing unit, of the computer. They store data and instructions currently being operated on by the computer. Depending on the CPU in the computer, or even the operating system, different amounts of registers are available for the program to use. Therefore, the registers named in the code, which will be referred to as source registers, or SRs, will need to be replaced by the specific register present in the CPU that will be used when the program is run. If the computer only has 3 physical registers, or PRs, the above code could not run, as it uses 5 registers. Thus, we must find a method of ‘allocating’ PRs to each instruction by either storing excess values temporarily in computer memory or through some other methods when it is not needed in an operation. For example, the following code could give you the same values only using 2 registers

loadI 1 => r0

loadI 2 => r1

add r0, r1 => r1

loadI 3 => r0

add r0, r1 => r02Methods

There were two main parts of this register allocator: a naive allocator and an optimized one built from the naive version. The naive allocator translates source registers into physical registers, and excess values are stored in the computer’s memory to be retrieved later. The optimized allocator expands upon this by optimizing the storing and retrieving depending on the context intended to reduce the runtime of the allocated code.

Naive Allocator

The Naive allocator follows the algorithm laid out in class and the algorithm outlined by Keith D. Cooper and Linda Torczon in Engineering a Compiler. The first step involved traversing up from the bottom of the ILOC code, where the last instruction is considered first. Source registers (in the original code) are assigned virtual registers (VRs) and their next use is calculated. Virtual registers represent the life cycle of whatever value is stored in it’s corresponding source register. When a source register is assigned a value it gets a new VR assigned to it, and the next use of a VR can be assigned by tracking the last time it was encountered. Thus, the original code would look like this:

loadI 1 => vr3

loadI 2 => vr4

loadI 3 => vr2

add vr3, vr4 => vr1

add vr1, vr2 => vr0Once the VRs are assigned and last use is calculated, we can begin allocation. This process involves traversing through the instructions from the top down, and assigning ‘free’ PRs. When a VR is no longer used and it is assigned to a a PR, the PR will be ‘freed’ for use. When there are no more free PRs, the PR with the farthest next use will be ‘spilled’ into memory. ‘Spilling’ a register requires adding additional instructions to store that value. The value can then be retrieved when the VR that was spilled is needed using more code insertion. When building the naive allocator, there was only one change from the provided algorithm which was adding a ‘PRnext’ table to keep track of the next use of each of the PRs to make spilling a bit easier.

Optimized allocator

There were three different optimizations implemented: Rematerialization, Respilling, and Clean Value tracking.

Rematerialization

In the code provided in the problem statement, the loadI instructions will load the provided integer value into a register. We know that a VR defined using a loadI must have that integer’s value as long as it is alive. Instead of storing the integer in memory when we need to spill a PR, we can simply overwrite the PR and instead track the constant value in the allocator. Thus, we can bring that value back through ‘rematerialization’. This was done by creating a new table VRrem to keep track of VRs that are rematerializable. VRrem is then populated during the code iteration whenever a loadI instruction is encountered. Thus, whenever a rematerializable value needs to be restored, we can just insert a new loadi instruction to retrieve it, instead of loading the memory address to a register and then loading from that memory address. This replaces 6 cycles of work with only 1.

Respilling

Values that are spilled are stored to an area of memory dedicated to spilling, and so the values will continue to exist in memory even after it is retrieved. Thus, we can check if the value we are about to spill already exists in memory, and if it does we don’t need to spill it. Spilling operations take 3 cycles of work, and restoring takes another 3, so this replaces 6 cycles of work with 3. This is done using the same table we populate whenever we spill, VRtoMemory, which tracks the memory locations of each VR that has been spilled. If the VR has a value in the table, then it has already been spilled and therefore does not need to be spilled again.

Clean Value Tracking

load instructions retrieve a value at a memory location and store it in a register. User memory is memory that the user directly accesses in the original code, not memory used for spilling. A clean value is the result of a load instruction from user memory that meets two conditions: the memory location is known, and the location has not been modified (dirtied) by a store to that location before it’s next use. When you can ensure both conditions, we can replace 6 cycles of work with 3 by not storing the value and instead reloading it from user memory. To do this, we first must label VRs as ‘dirty’ or not. This required adding a ‘dirty’ field to operands, and when we are calculating next use we will mark a VR as ‘dirty’ if there is a store operation between it and it’s next use. Then, when the allocation code we can set its VRtoMemory to the rematerializable (known) value of it’s user memory location.

Choosing a PR Heuristic

When we need to choose a PR to spill (when there are not enough ‘free’ PRs), the naive allocation algorithm simply finds the PR with the farthest next use. Because of these new optimizations, spilling certain PRs may be more efficient than others. I came up with this very simple heuristic to choose which PR to spill:

score = cost - (PRnext - current instruction index)There are 3 costs:

- 1 for rematerializable values

- 3 for clean values / respilled values

- 6 for everything else

We then calculate the score for each PR, and choose the PR with the lowest score is spilled.

Complexity

The allocation algorithm iterates through the source code three times. Once to actually parse the original code, once to assign VRs, and once more to actually allocate PRs.Thus, this is a O(n) algorithm.

Interestingly, it was O(n^2) at one point because the instructions were stored in a singly-linked list that required a full-list traversal in order to add an instruction to the list, however this was remedied by switching to a doubly-linked list that keeps track of the end of the list.

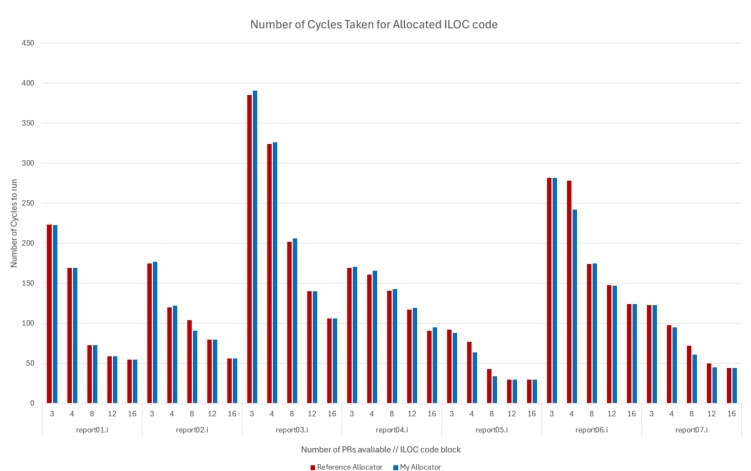

Results

| Cycle times Allocated | Cycle times Allocated | Cycle times Allocated | Cycle times Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Report File | PRs | Reference Allocator | My Allocator |

| report01.i | 3 | 223 | 223 |

| report01.i | 4 | 169 | 169 |

| report01.i | 8 | 73 | 73 |

| report01.i | 12 | 59 | 59 |

| report01.i | 16 | 55 | 55 |

| report02.i | 3 | 175 | 177 |

| report02.i | 4 | 120 | 122 |

| report02.i | 8 | 104 | 91 |

| report02.i | 12 | 80 | 80 |

| report02.i | 16 | 56 | 56 |

| report03.i | 3 | 385 | 391 |

| report03.i | 4 | 324 | 326 |

| report03.i | 8 | 202 | 206 |

| report03.i | 12 | 140 | 140 |

| report03.i | 16 | 106 | 106 |

| report04.i | 3 | 169 | 171 |

| report04.i | 4 | 161 | 166 |

| report04.i | 8 | 141 | 143 |

| report04.i | 12 | 117 | 119 |

| report04.i | 16 | 91 | 95 |

| report05.i | 3 | 92 | 88 |

| report05.i | 4 | 77 | 64 |

| report05.i | 8 | 43 | 34 |

| report05.i | 12 | 30 | 30 |

| report05.i | 16 | 30 | 30 |

| report06.i | 3 | 282 | 282 |

| report06.i | 4 | 278 | 242 |

| report06.i | 8 | 174 | 175 |

| report06.i | 12 | 148 | 147 |

| report06.i | 16 | 124 | 124 |

| report07.i | 3 | 123 | 123 |

| report07.i | 4 | 98 | 95 |

| report07.i | 8 | 72 | 61 |

| report07.i | 12 | 50 | 45 |

| report07.i | 16 | 44 | 44 |

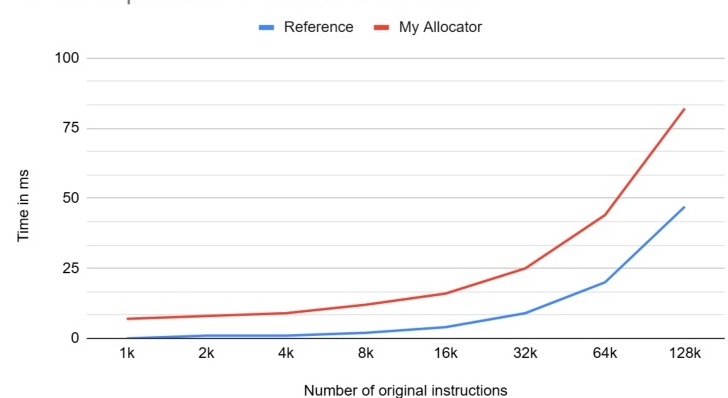

Time comparison with reference allocator

While my allocator and the reference allocator performed relatively similarly, mine still appears to lag behind in execution speed. Looking at the actual performance of the allocated code, On report02.i, my allocator seems to perform very slightly worse on 3 and 4 registers (2 cycles worse), yet on 8 registers it performs 13 cycles better. On report06, I beat the reference allocator by 36 cycles on 4 registers, but it beats me by 1 cycle on 8 registers.

It seems like the differences are mostly arbitrary, and this is likely just due to different heuristics used for choosing a PR to spill. There might be a slight pattern on the reference beating mine on fewer registers, but there isn’t enough data here to prove that.

As far as execution speed, it could be for any number of reasons. The compiler used to compile each allocator is my guess, though it could have something to do with my linked list implementation or other memory-related/allocation problems.

Experience

My mistakes in the original scanner and parser, as well as in implementing the actual allocator led to this taking much more time than expected. The first issue arised with an issue in my parser that led to issues with immediate values not being tracked properly. This was remedied, and I ended up refactoring a bit of the parser implementation afterwards. The actual storage of the instructions was a big issue at times. First, I used a linked list to store instructions,and this led to a O(n^2) runtime that was unacceptable. Then I switched to an array because it seemed like it would be easier to work with. This switch required a major refactor, and while it worked beautifully for a while, when I finally tested it on larger inputs, it became another issue simply due to the reallocations of the array when it became full. Fixing this would have been easier than doing what I did next, which was swapping back to a linked list, but this time making it a doubly-linked list. That was a bad time.

Another thing that one might notice when looking through my codebase is the amount of tables I used to keep track of things that really weren’t necessary. For example, I have a PRtoVR table, but I also have a VRtoPR table. If you look through the commented out code placed around, you will find remnants of tables such as SRtoVR, VRspilled, lastStore,and lastModified. None of these were necessary in the final implementation and in the end simply overcomplicated the project.

Using gdb to debug was very useful in figuring out what had gone wrong whenever the program would hang. Stack overflows, segmentation faults, stack smashing, all of these problems were at the very least helpfully discovered by this wonderful tool.

If I had to start over, I would plan out everything I needed from the ground up, because developing the allocator with guesswork and changing the .h file extremely often leads to headaches and unnecessary work. Another important thing is just to keep your codebase organized. This is not a small project, and once things start piling on top of each other you will need to be able to go back and change older code without needing to refamiliarize yourself with the entire algorithm for parsing. The cost of disorganization on development time grows exponentially and it becomes more and more difficult to track down bugs as the codebase grows.

References

Cooper, Keith D., and Linda Torczon. “Register Allocation.” Engineering a Compiler, 2nd ed., vol. 1, Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco, CA, 2011, pp. 679–723.

Testing utilities provided by Seth Fogarty of Trinity University.

Final report: Allocator Report.pdf